-

(818) 833-8737

13521 Hubbard St.Sylmar, CA 91342

- Login

A Mother’s Long Struggle to Help Her Homeless Son

Posted on 03/23/2023

by

A Mother’s Long Struggle to Help Her Homeless Son

This is part one of a two-part series.

Gina Pérez’s 43-year-old son Joseph Zamora has lived on the streets of San Fernando/Sylmar for nearly half his life, suffering from schizophrenia whose diagnosis came too late for effective treatment after years of self-medicating. Seeing her son caught in a revolving door of homelessness, incarceration, and hospitalizations over two decades, a cycle that is typical for the mentally ill homeless population, Pérez knows she is his only lifeline.

After work, she looks for her son every day and brings him clean clothes, blankets, and food. Joseph’s mental illness is debilitating and keeps him gripped in the belief that he is safest on the street.

Often crippled with despair and paranoia — the mentally ill homeless population is one of the hardest to reach and toughest to treat. Hospitals oftentimes turn them back onto the street after a few days without follow-up care.

Pérez hopes a new California law will bring more help for Joseph this year.

Joseph Zamora is pictured near the intersection of Hubbard Street and Glenoaks Boulevard in San Fernando. Zamora, who just turned 43 this week, suffers from schizophrenia and has been living on the streets for the past two decades. Photo: Gina Pérez

“My son is a good candidate for the CARE Courts,” said Pérez, sitting in the living room of her San Fernando apartment on a recent day. She is referring to a court-ordered treatment system being phased in under the Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment (CARE) Act. Signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom in September, the law would force some people with untreated schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses into housing and treatment.

Homelessness and Legislation

The CARE Act applies to all mentally ill people in California but the legislation was enacted at a time when residents and businesses were clamoring for solutions for a homeless crisis that has impacted communities throughout LA County. The “unhoused” population that numbers nearly 70,000 have been visible beyond skid row, riverbanks, and parks for some time. Living under freeway overpasses, on hillsides, and on alleyways, a large percentage struggle with mental illness and experience mental health issues living on the street.

One in every four homeless adults in LA County has a severe mental illness like a psychotic disorder and schizophrenia, according to a 2020 study by Stanford University. The survey showed that 27 percent also had a long-term substance use disorder and that a higher percentage of the chronically homeless have a drug addiction, a severe mental illness, or both. As of last year, there were almost 70,000 homeless people in the county, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, a leading agency managing federal, state, county, and city funds for homeless programs in the region.

Some mentally-ill homeless individuals can often be spotted on public transportation. These days in the San Fernando Valley, riding the Metro Red Line between downtown Union Station and North Hollywood Station means sharing subway cars with unhoused individuals who act disruptively talking out loud to themselves or imaginary people, sleeping onboard, lacking basic personal hygiene, and doing drugs. In some cases, they relieve themselves onboard or become violent.

People living on the street like Joseph, with untreated schizophrenia, could be stabilized with health services, medications, and housing, but this support isn’t readily offered and may come only after an arrest or through conservatorships or institutionalization.

Troubles with the Law

Joseph has been arrested at least 20 times for trespassing, petty theft, and other crimes, sometimes spending between one and three years in jail, hospitalized for various ailments, and in a few conservatorships, all of which meant a temporary roof over his head and regular medication, according to his mother. Then he would be back on the streets, most times near the intersection of Hubbard Street and Glenoaks Boulevard, pushing a shopping cart with his belongings, often disheveled, sometimes trying to stay warm and dry like during the recent cold and rainy days.

Now CARE Courts could offer Joseph treatment and housing for up to two consecutive years. His mother is ready to refer her son as soon as the court process is in place.

A candidate for CARE Courts can be petitioned by a family member, county and community-based social services, behavioral health providers, or first responders like police officers, firefighters, and paramedics.

One of the CARE Act authors thinks Joseph qualifies for services under his legislation. “Families are desperate for something [new] to be done for their loved ones [suffering from severe mental illness],” said Tom Umberg (D-Garden Grove) in a phone interview.

He explained that seven counties are part of a pilot program to set up CARE courts by Oct. 1. They include Orange, San Diego, and Riverside counties, with Los Angeles joining two months later.

December cannot come soon enough for Pérez.

Impact on the Family

For two decades, the 59-year-old woman’s life has been an endless rollercoaster, knowing her son was living on the streets. But it wasn’t always the case.

She recalls much better times when Joseph was an energetic, happy little 4-year-old who was featured in the mural “LA Freeway Kids,” painted for the 1984 Olympics along the Hollywood Freeway in downtown LA and depicting seven children romping. Pérez keeps a framed poster of that mural in her living room. She points at the boy in a white shirt, red shorts, and tennis shoes and says with pride, “That’s Joseph. He was always a clean-cut kid growing up.”

Through the years, Gina Pérez has taken photos of her son Joseph Zamora to document his life and for his protection. Photo: Gina Pérez

Joseph’s first signs of mental health issues appeared in the early 2000s when his family lived in Reseda. The then-teen attended Granada Hills High School. A few years earlier, his father abandoned the family, which included Joseph’s younger sisters, Mandy and Anjelica. “He never recovered from it,” says his mother, adding her son later started using drugs regularly. In 2002, he would be diagnosed with schizophrenia. As her son abused drugs and neglected his mental illness, Pérez kicked him out of the house several times, hoping that “tough love” would set him straight.

It didn’t work.

The year 2003 marked the first time Joseph didn’t have a roof over his head, says Pérez, explaining he “became homeless in spurts.” About two years later, police arrested him for criminal activity, one of many times that would see him in and out of jail.

Things would still get worse. Joseph’s behavior spiraled out of control in 2006 when he slapped one of his sisters at home, leading their mother to file a restraining order against him. Pérez later moved to San Fernando but didn’t give the new address to her son.

Last year, one of Pérez’s neighbors filed another restraining order against Joseph for an incident when he showed up unannounced. “He’s now been homeless since May of 2022,” says his mom.

Then in February of this year, Joseph also hit his mother on the head while she sheltered him from the rain in her car. He was sleeping in the passenger seat and woke up agitated, according to Pérez. “His psychosis state creates those incidents,” she says. Pérez had him arrested and out of precaution she went to a local hospital to get herself checked out. She was fine.

Stigmatization of Mental Conditions

Looking back 20 years, Pérez realizes how little she understood mental health. A daughter of Mexican immigrants, she says mental illness is still greatly stigmatized among the Chicano and Latino communities. Eventually, with the help of a relative who was a social worker, Pérez came around to accept that her son suffered from a medical condition.

Sometimes Pérez wonders if she should have paid more attention when teachers said her son talked too much in classes. “Should I have got him tested for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or ADHD,” Pérez says she asked herself often. “Should I have taken him to the doctor and asked more questions?” She recommends other parents do what she herself didn’t. “All these things can contribute to what happens to them later in life,” Pérez says.

Pictured:

• Joseph Zamora is pictured near the intersection of Hubbard Street and Glenoaks Boulevard in San Fernando. Zamora, who just turned 43 this week, suffers from schizophrenia and has been living on the streets for the past two decades. Photo: Gina Pérez

• Through the years, Gina Pérez has taken photos of her son Joseph Zamora to document his life and for his protection. Photo: Gina Pérez

Part two of this article will be published by the sanfernandosun.com next week. The Sylmar Neighborhood Council will also be sharing.

2025 Sylmar Community Holiday Party

Sign-Up • Receive Agendas

Upcoming Meetings & Events

-

Dec17

Cancelled

Equestrian Committee Meeting - Dec17 Free Produce/Food Distribution at Olive View/UCLA Medical Center 9:30am - 11:30am

- Dec18 FREE MOVIE NIGHT AT THE SNC Council Office

- Dec22 Free Produce/Food Distribution at Olive View/UCLA Medical Center 9:30am - 11:30am

- Dec22 Telescope Nights at Sylmar Library

Sylmar Community Calendar

MyLA311

My LA 311

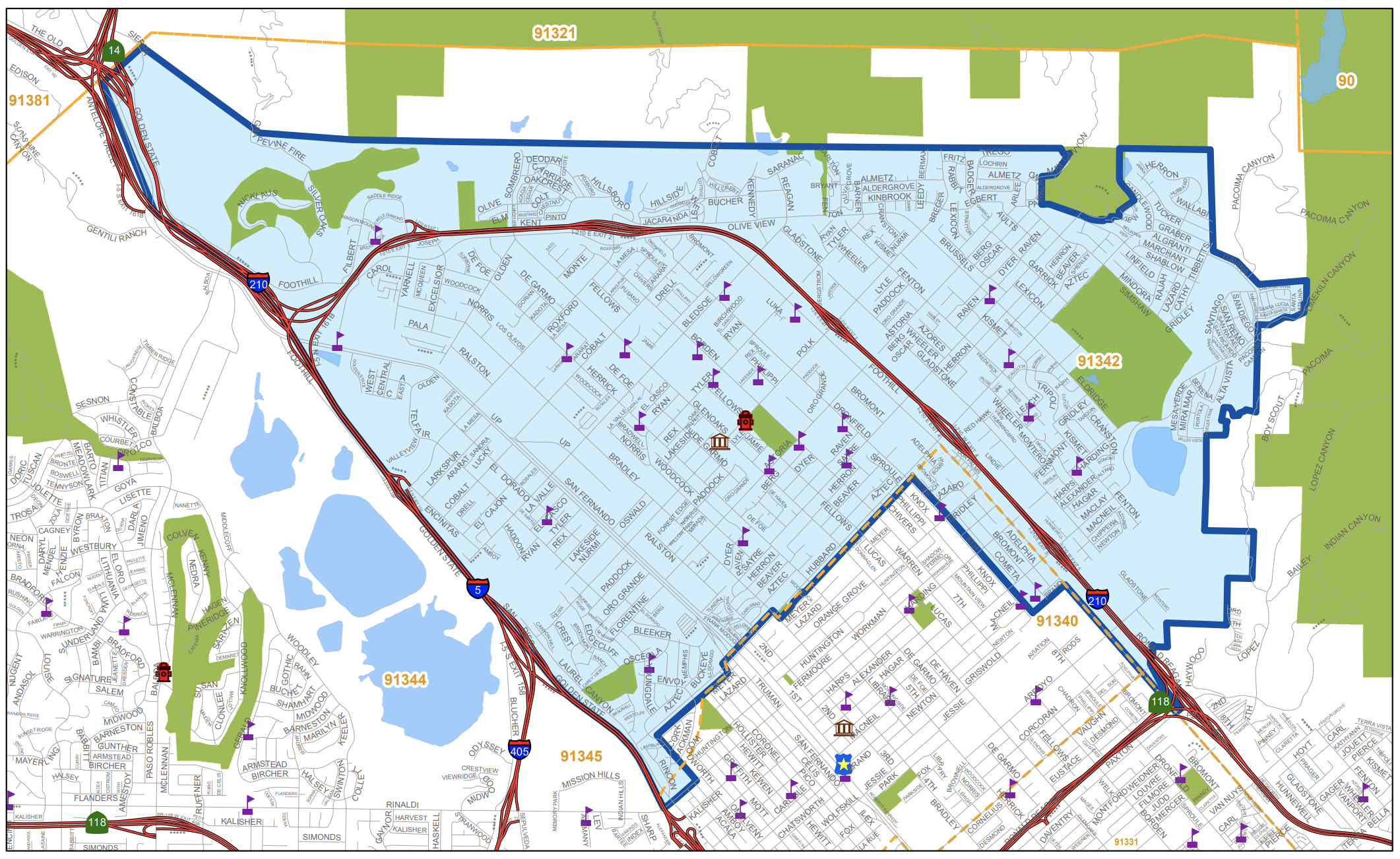

Area Boundaries and Map

View our neighborhood council boundaries for which we deal with.

EMPOWER LA

NEIGHBORHOOD COUNCIL CALENDAR & EVENTS

The public is invited to attend all meetings.

NEIGHBORHOOD COUNCIL FUNDING SYSTEM DASHBOARD

SUBSCRIBE TO NC MEETING NOTIFICATION