-

(818) 833-8737

13521 Hubbard St.Sylmar, CA 91342

- Login

Tataviam First People - Sylmar, LA City, LA County

Posted on 07/11/2025

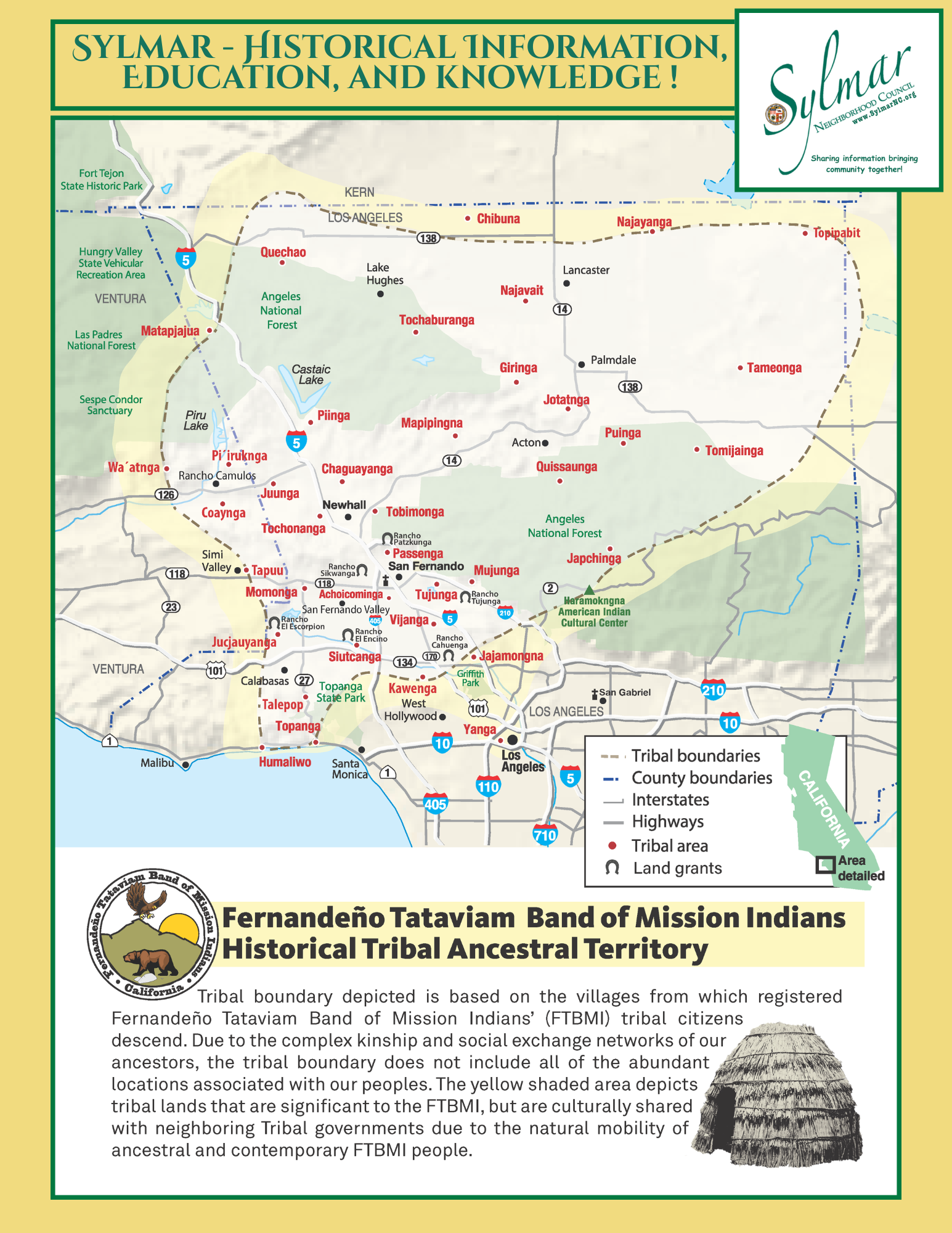

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians is a native sovereign nation of northern Los Angeles County.

LA County, LA City, and the community of Sylmar recognizes and acknowledges the first people of this ancestral and unceded territory of Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians that is now occupied by our community of Sylmar honors their elders, past and present, and the descendants who are citizens of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians. We recognize that the Tribe is still here and we are committed to lifting up their stories, culture, and community.”

The citizens of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians are the people of northern Los Angeles County. After thousands of years, foreign powers began colonization in the late 1770s with the arrival of the Spanish followed by the establishment of Mexico and the United States. Despite settler colonization, the Tribe continues to operate as a tribal community.

Before Colonization

Prior to colonization, the ancestors of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians originally inhabited the villages originating in the Simi, San Fernando, Santa Clarita, and Antelope Valleys. Before settlers arrived, the village organization structure in Southern California was unique in that there was no single leader that ruled over all the villages. Instead, each village was an autonomous self-governing entity that had its own structure of leadership, cultural practices, economy and territory. To strengthen economic and social relations with villages outside of their own, the members of a village practiced exogamy and thus, spoke the languages and dialects that existed at the neighboring villages. Villages were linked by their beliefs about the afterworld, and thus, were known as regional groups. For example, the villages located in the Santa Clarita Valley and surrounding mountain ranges were sovereign, but their beliefs about the afterlife linked them together as the Tataviam people. The name Tataviam comes from the word “táta’viam,” which is the name given to them by their Kitanemuk neighbors to the north known as the Tejon Indian Tribe.

Spanish Colonization

Mission San Fernando Rey was established on September 8, 1797. Enslavement at Mission San Fernando by the Spanish drastically changed the daily lives of the Native Americans who would be called Fernandeños. Families were separated, children were married off, sacred sites were demolished, culture was suppressd, traditional ways of life were destroyed, food sources were removed by environmental degradation from invasive species, and the Fernandeños were massacred through Spanish-brought disease, hunger, violence, and slavery. The life of a Fernandeño person was completely overseen and controlled by the Mission Padres. For example, the Fernandeños could not leave the Mission grounds without the Padres’ permission and often received corporal punishment for violating the rules. Against incredible odds, some Fernandeños survived and maintained aspects of their cultural practices privately while others refused to identify publicly as Native as an act of survival.

Mexican Colonization

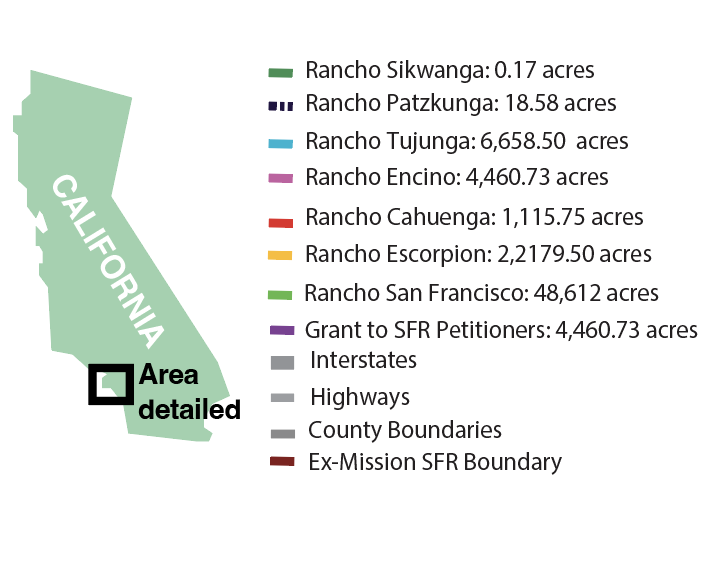

In 1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain and California fell under the jurisdiction of the First Mexican Empire. After the Missions were secularized by Mexico, approximately 50 surviving Fernandeño leaders negotiated for and received several land grants amounting to over 18,000 acres (10% of the San Fernando Valley) that were held in trust by the Mexican government. These land grants included Rancho El Escorpion (Chatsworth), Rancho Encino (Encino), Rancho Cahuenga (Burbank), and Rancho Tujunga (Tujunga), and were meant to be preserved in the American period.

(Map of Mexican Land Grants. The Fernandeño Historical Indian Tribe petitioned for and received land grants located on their ancestral and historic villages.)

American Colonization

Throughout the 1800’s, the United States was on a mission to eradicate Indigenous nations. In the era of California’s State and Federally funded Genocide and campaign to exterminate California Native American people, Fernandeños lacked U.S. citizenship and yet, fought to defend their lands in local state courts for several decades to no avail. In the first years of its statehood, California also passed the 1851 Land Claims Act, which would pass lands into public domain that was not filed within a two-year period. Land in northern Los Angeles County, particularly areas with natural water sources such as the Native-owned land grants, became extraordinarily valuable. The Fernandeño ancestors, who could not read or write English, lost their lands within this two-year period to encroaching settlers. Several Fernandeños had cases heard in the Los Angeles Superior Court [for example, see Porter et al v. Cota et al.] but the local state courts were against the Fernandeño ancestors’ claims to the land, which made it impossible for the San Fernando Mission Indian defendants to affirm rights to land that would have formed the foundation for a reservation.

By 1900, the Tribe lost all its lands and members were left as refugees on their own homelands. As result of the land evictions, the Tribal leaders were defended by attorneys commissioned by the federal government. For example, official representatives of the United States, such as Assistant United States Attorney G. Wiley Wells and United States Special Indian Agent and Special Attorney for Mission Indians Frank D. Lewis, pursued land for the evicted Fernandeños. Yet, the historic Fernandeño tribe was not made a federally recognized tribe. Today the Tribe, the descendants of the historic Fernandeño Indian tribe, consist of 3 surviving lineages of 900+ people. These lineages are known by the surnames of their family leaders: Ortega, Garcia, and Ortiz.

Every single part of the landscape was and continues to be of great importance to the Tribe. Today, the Tribe views the lands of Tataveaveat as a sacred cultural space containing thousands of years of activity, memories, stories, and ancestral lifeways.

Porter et al v. Cota et al

On June 1, 1876, a group of Fernandeños and married relations purposely "occupied" their village land to test American law. They were taken to court by ex-California Senator Charles Maclay and later the judge, a relative of Maclay, reaffirmed Maclay’s rights to the land. As result, the Fernandeños were evicted from present-day San Fernando and surrounding areas.

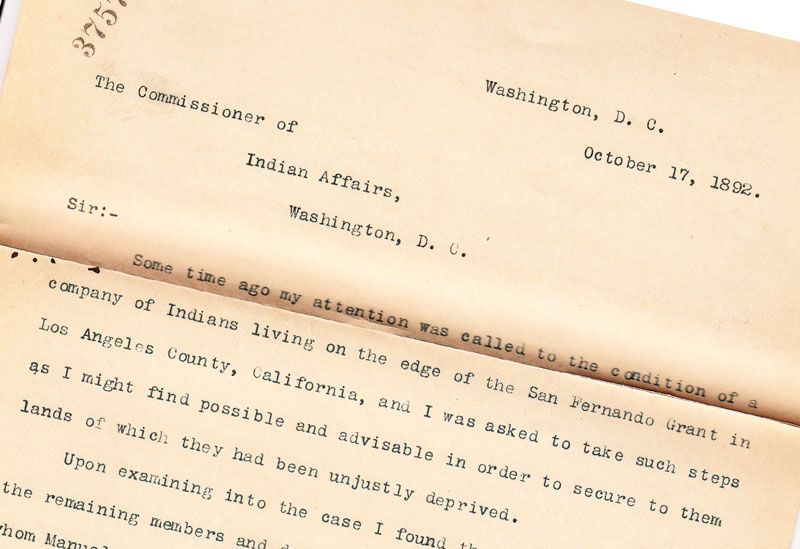

U.S. Attorney Represents Fernandeños

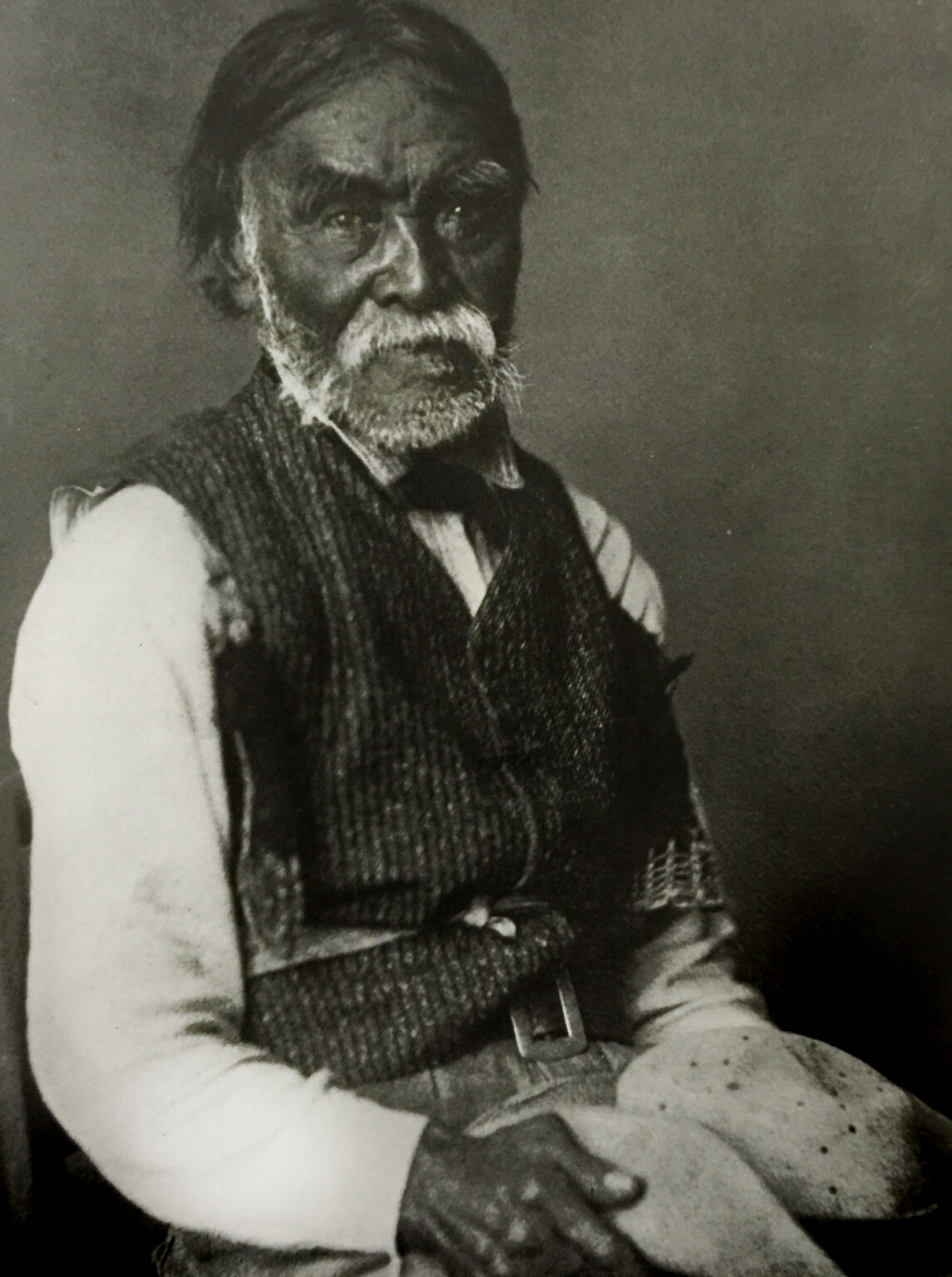

In 1885, U.S. Special Attorney for Mission Indians, Guilford Wiley Wells represented Rogerio Rocha and the Fernandeños in an official government capacity to prevent the Tribe's eviction from Indian land. On November 2, 1885, Wells’ petition on behalf of Rogerio Rocha and the Fernandeños' land interests was denied in Los Angeles County Superior Court.

Federal Agent Recognized Fernandeños

Frank D. Lewis, the Special Assistant U.S. Attorney for Mission Indians, pursued a solution for the Fernandeños' eviction from San Fernando through the length of his tenure until 1897.

For more information, education, and knowledge -

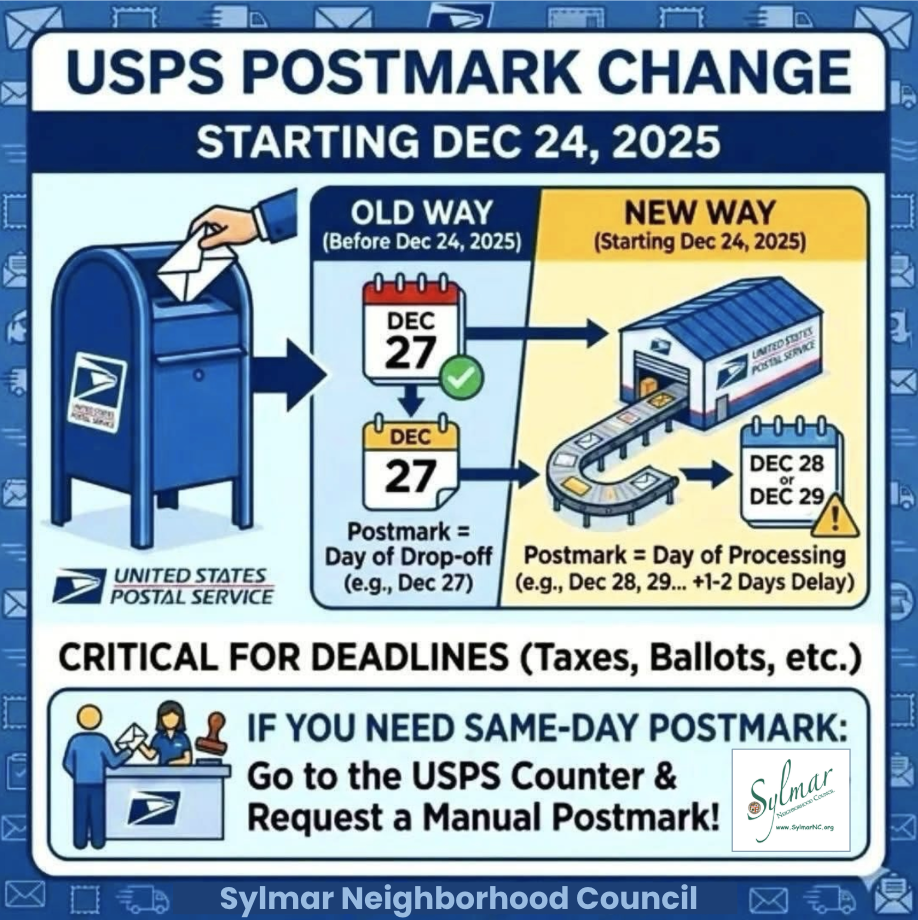

US Post Office Information

Small Business Saturday • May 9th

Sign-Up • Receive Agendas

Upcoming Meetings & Events

Sylmar Community Calendar

MyLA311

My LA 311

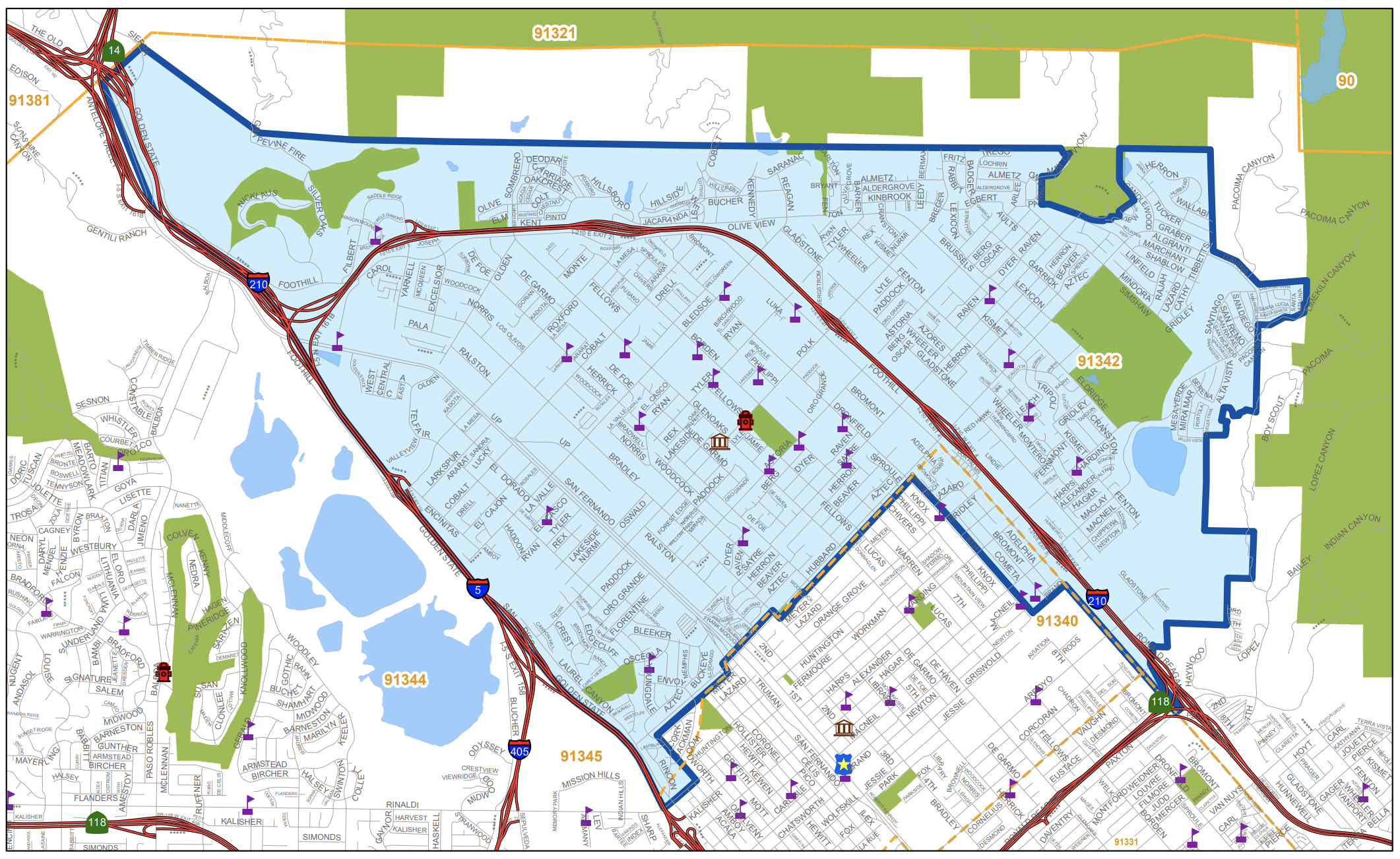

Area Boundaries and Map

View our neighborhood council boundaries for which we deal with.

EMPOWER LA

NEIGHBORHOOD COUNCIL CALENDAR & EVENTS

The public is invited to attend all meetings.

NEIGHBORHOOD COUNCIL FUNDING SYSTEM DASHBOARD

SUBSCRIBE TO NC MEETING NOTIFICATION